The recent Ebola outbreak and the ongoing AIDS epidemic are much more than mere medical challenges—they are economic challenges, challenges of poverty and inequality, and challenges to people’s way of life and dignity. What can Japan do to deal with these and other challenges we face in our society and around the world?

The recent Ebola outbreak and the ongoing AIDS epidemic are much more than mere medical challenges—they are economic challenges, challenges of poverty and inequality, and challenges to people’s way of life and dignity. What can Japan do to deal with these and other challenges we face in our society and around the world?

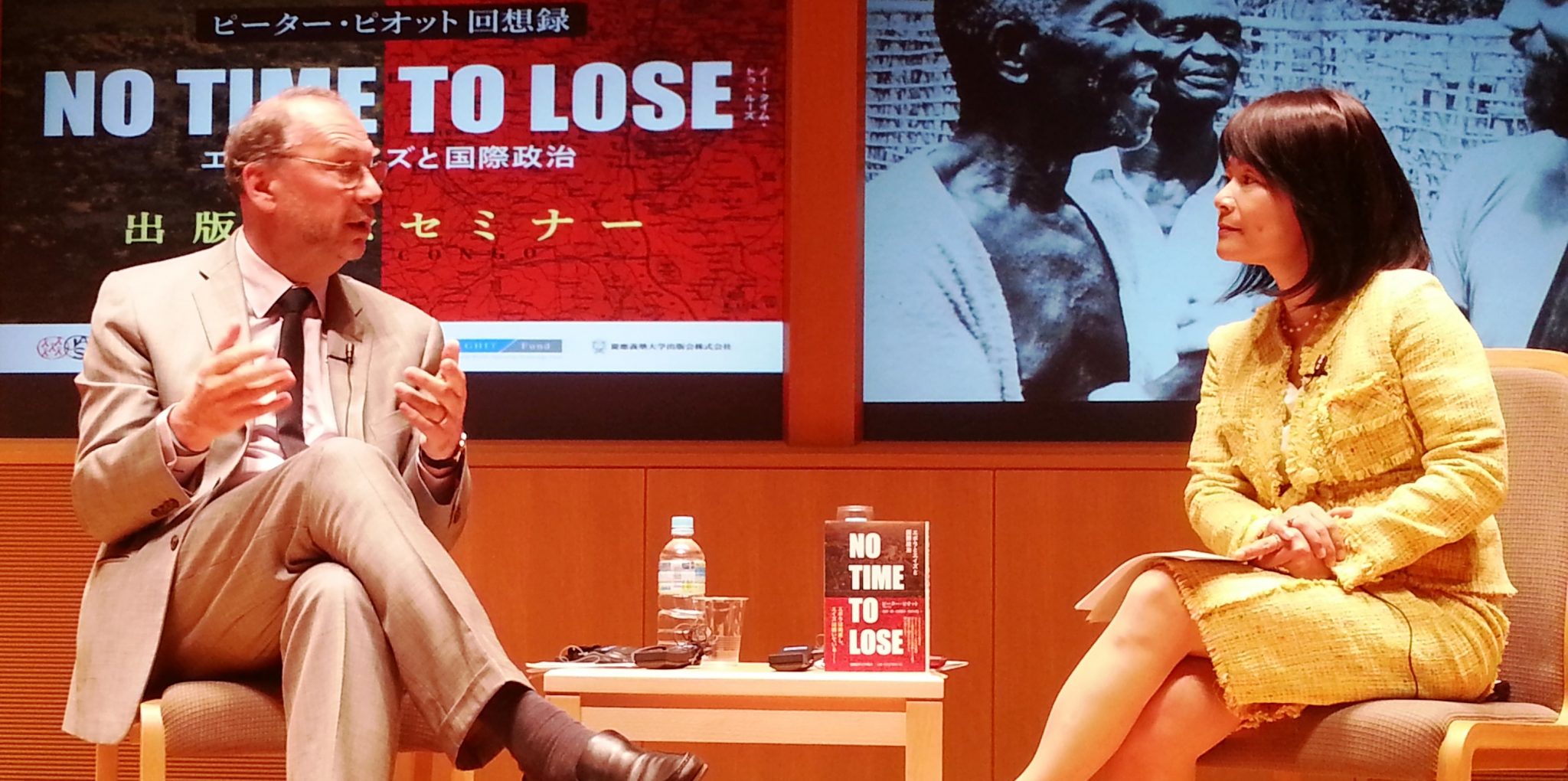

On April 17, Peter Piot, currently the director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, whose memoir No Time to Lose: A Life in Pursuit of Deadly Viruses was recently published in Japanese, spoke in Tokyo about his experience at the front lines of the fight against communicable diseases. As a young researcher in his 20s, Dr. Piot was part of a team that discovered the Ebola virus in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo). After that encounter, he dedicated himself to treating communicable diseases in Africa at a time when AIDS first started appearing on the scene, and went on to become the founding executive director of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) when it was launched in 1996.

Speaking as a scientist, as a doctor, as the head of an international agency, and as an activist who understands the needs of communities around the world, Dr. Piot shared his thoughts on the importance of collaboration beyond borders, nationalities, political beliefs, and interests; the necessity of cross-sectoral and cross-organizational cooperation in combating global crises such as Ebola and AIDS; and the implications that the battle against infectious disease has for other domestic and global challenges.

The seminar opened with Miki Ebara, editor-in-chief of NHK World’s Newsline, interviewing Dr. Piot about his book, his early work with the Ebola virus, and later his frustrations and accomplishments as one of the top international bureaucrats fighting the spread of HIV/AIDS. “I was lucky that soon after I assumed the position, antiretroviral (ARV) drugs were developed and AIDS became treatable,” said Dr. Piot. He concentrated his efforts on providing the newly available ARV therapy (ART) to developing countries. Fighting hard against skeptics who claimed it would be impossible to provide expensive ART in Africa, given the weak health systems there, he led negotiations with pharmaceutical companies to procure the drugs at reduced prices and started pilot projects that provided ART in Africa to demonstrate that it was actually possible. In 2000, working with colleagues, he successfully brought AIDS to the agenda of the UN Security Council, placing it on the public health agenda for the first time. He recalled that was the real breakthrough that led to the reduced price of ARV drugs and the establishment of new funding mechanisms such as the Global Fund.

He also shared his experience of waiting to get the results of an HIV test—ultimately negative—after accidentally getting stuck with a needle that was thought to have HIV-infected blood on it. The anxiety of waiting for the results drove him to create an environment that encourages tests with quicker results in order to reduce the waiting time that others would have to face. That ability to look beyond merely the scientific and medical aspect of the diseases he has worked on to understand the people they infect and the ways in which they affect their lives is a theme that flowed through the session in the same way that it flows through his memoir.

Following Ms. Ebara’s interview, three young Japanese leaders spoke with Dr. Piot in the final session of the seminar: Takuma Kato, deputy medical director, Department of Global Health/Pediatrics at Saku Central Hospital; Yosuke Takaku, representative director of the Japanese Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS; and Yuka Iwatsuki, president of Action against Child Exploitation. Below are several excerpts from the discussion.

From Clinician to International Bureaucrat

Kato: What surprised me most is your unconventional career path, from a clinician and researcher to the executive director of UNAIDS. When you were working in Africa, you said you didn’t have any desire to work in politics, so you turned down invitations to work in AIDS policymaking. However, in the end, you decided to run for and were elected to the position of executive director of UNAIDS. What made you change your mind?

Piot: Switching to a completely different field was extremely difficult, to be honest. However, after doing research for many years, I went through a midlife crisis. I started to wonder how long I could continue to study this unfolding disaster. While I had presented a lot of work, I still felt like no one had taken any concrete measures against the spread of AIDS. This was a disaster and we had to do something about it.

I was excited when UNAIDS was established because it meant that concern about AIDS had increased. But I never thought that I would be part of it because I wasn’t interested in becoming a UN bureaucrat. However, when I found out who the other candidates were, it was clear that they didn’t know much about AIDS. I decided to run for the position because how is someone who doesn’t know much about AIDS and who has never worked in the field going to appeal to politicians? After I became director of UNAIDS, I faced many challenges, but my strong desire to do something about AIDS kept me going. It was lonely, but I was able to find allies to work with to achieve our shared goal.

From the Point of View of People Living with HIV

Takaku: As Dr. Piot said, we have been very fortunate in Japan. Following the HIV-tainted blood scandal, the AIDS treatment and welfare system was quickly corrected and cutting-edge treatment spread across Japan. However, treatment alone could not solve all of the problems. People living with HIV shouldn’t be discriminated against or excluded from society. Those of us who live with HIV should raise our voices and work more closely with researchers and policymakers to improve the situation.

Reading this book, I was struck by the way that you addressed the topic of sex and sexuality without hesitancy or prejudice. However, this was 20 years ago. How were you able to do that during those times? How do we create more people like you?

Piot: I don’t recommend that anybody become like me because we are all unique. I was actually raised in a conservative family. However, a doctor’s job is to save lives, so where and how a patient contracted HIV—and if that is a good or bad thing—isn’t for me to judge. And that avoidance of judgment is a basic condition for trust between a patient and a physician.

I always want to understand what other people are thinking; therefore, I always try to listen. No matter which country I go to for an event, I always try to go out for drinks and talk to people afterwards. In Japan, I went to visit a gay bar in Shinjuku. By talking with people there, I not only get a better grasp of their situation, I also come to understand their mindset. It is a very anthropological approach, but I think nothing can replace listening to people.

Lack of Political Will

Iwatsuki: When I started working in the child labor movement in 1997, I came across a phrase by Kailash Satyarthi, last year’s Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He argued that poverty isn’t the reason why child labor won’t end. It’s because of the lack of political will. If just 1 percent of the money that is spent on the military were put toward humanitarian aid, more people could be saved. But there is no political will to allocate resources in such a way. And now that I am working on child labor issues, I am aware that it is extremely difficult to arouse political will where it is lacking. You have achieved a lot in the fight against AIDS, but what do you feel has been the most meaningful thing thus far?

Piot: Yes, I agree with you that political will is very important. The two most important things in the fight against AIDS are probably having a strategy and creating a movement. Once a movement is created and political will is aroused, money will come. I think this also applies to the fight against child labor. Strategically, other than emphasizing about how horrible child labor is, it is essential to come up with a solution and convince people that they are part of the solution and we can do something to improve the situation. Also, sometimes it is OK to bend the rules when trying to achieve a huge goal because you can always apologize later.

Information

| Date/Time: | April 17, 2015 18:30~20:00 (followed by a reception) |

| Location: | Keio University, Mita Campus |

| Organizer: | Japan Center for International Exchange/Friends of the Global Fund, Japan |

| Co-organizer: | Keio University Department of Philosophy and Ethics |

| Collaborators: | Japan AIDS & Society Association, Global Health Innovative Technology Fund, Keio University Press |

| Language: | English/Japanese (simultaneous interpretation) |

Program

Introductory Remarks

Kiyoshi Kurokawa, Adjunct Professor, National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS); Chair of the Board, Global Health Innovative Technology (GHIT) Fund; Chairman, Health and Global Policy Institute

Discussion: Author’s Reflections

Peter Piot, Director, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; former Executive Director, UNAIDS

Miki Ebara, Editor-in-Chief, NEWSLINE, NHK WORLD

Dialogue with Young Leaders: What the Next Generation of Leaders Can Take From No Time to Lose

Peter Piot

Takuma Kato, Deputy Medical Director, Department of Global Health/Pediatrics, Saku Central Hospital

Yosuke Takaku, Representative Director, Japanese Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS

Yuka Iwatsuki, President, Action against Child Exploitation (ACE)

Moderator: Satoko Itoh, Managing Director and Chief Program Officer, JCIE

Closing Remarks

Akio Okawara, President and CEO, JCIE

Reception